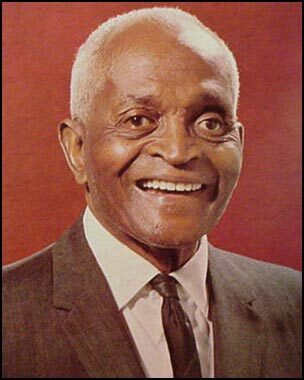

Marshall Keeble, Noteworthy Preacher

Let God rise up; let his enemies be scattered; let those who hate him flee before him. . . . The Lord gives the command; great is the company of those who bore the tidings . . . .” Ps. 68:1, 11 (NRSV). Various authors describe the life and legacy of one such person in Faithful Defiance: Marshall Keeble’s Life and Legacy (2025, C. Leonard Allen, ed.). Below is my very short summary.

Keeble’s preaching blended biblical rigor with parables and humor, and he rejected emotionalism in favor of rational conversion. Some sources indicate that his efforts led to over 40,000 baptisms and the founding of around 300 congregations, primarily within segregated Black communities. His success stemmed from various factors, including personal zeal, prayer, homiletical skill, and support from both Black mentors and White philanthropists—some of whom held racist views. Keeble navigated these tensions with humility and strategic silence: believing racial self-help and spiritual growth were his most effective tools, he never publicly opposed segregation.

Though Keeble had only a seventh-grade education, he excelled in memorization and public speaking. Keeble began preaching at Nashville missions and launched full-time evangelism in 1914. Motivated by his desire to preach the gospel in what he called “destitute places,” he traveled extensively—even on foot—to reach remote congregations. In his first five years, by his count, he preached over 1,100 sermons, baptized 457 people, and traveled more than 23,000 miles. His wife Minnie was a vital partner in ministry, often leading song services.

Laws and practices mandating segregation made Keeble’s travel more difficult. At “Whites only” motels, Keeble’s sometime travel companion, Willie Cato, a younger White minister, registered as the guest and snuck Keeble into their room after dark. Discovering this, the night manager at one place evicted Keeble and Cato in the middle of the night. Keeble responded with grace and faith, telling Cato, “We don’t stay where we are not wanted” and “You know you have to forgive him, right?” Years later, the motel manager sought forgiveness, highlighting the enduring impact of Keeble’s quiet dignity and moral leadership.

Keeble supported the idea of formal training for Black ministers and eventually served as president of an influential one, the Nashville Christian Institute (NCI). There, Keeble mentored Fred Gray, a future civil rights attorney, who - in contrast to Keeble’s quiet diplomacy - adopted a bold stance against racial injustice. Keeble’s silence on segregation was both criticized and defended. While he believed the gospel could overcome prejudice, he feared that speaking out might jeopardize institutions like NCI, and this risk materialized. The end of racial segregation “opened doors of opportunity for Black students” in schools once closed to them but this “quickened the collapse” in 1967 of NCI.

Keeble’s death in 1968 marked the end of an era. After his passing, Black church leaders increasingly rejected White paternalism, leading to more independence for Black Churches of Christ. And the post-Keeble era saw a shift toward a post-denominational, post-Christian cultural landscape, challenging churches to redefine their mission and identity. Throughout their history, Churches of Christ - both White and Black - have claimed a nondenominational vision. As the editor of Faithful Defiance notes, our time gives us “a new chance to live out what [we] think that means.”

On October 7, starting at 7 pm Eastern time, the Reading Circle (RC) will discuss Faithful Defiance via Zoom at this link. Information about this small group and others in our congregation is at Small Groups | Arlington Church of Christ. I encourage your participation, including in RC even if you have not read the book.